Last time, you decided that a silent protagonist is better than combat style ratings. Not by much! It was a 60/40 split, and I’m surprised/glad it was this close. We are now one decision closer to knowing the best thing. This week, I ask you to choose between a matter concerning movement, and what an enemy does in response to when and how you move. What’s better: an enemy which can’t see you but can sense you, or it only moves when you’re not looking?

Enemy which can’t see you but can sense you

You know you’re in trouble when a game removes an enemy’s sight. This inevitably means it’s so deadly that if it could see you, it would instantly murder you. Luckily, for some reason of biology or technology, it has to rely on other senses, usually hearing or sensing vibrations. You, ah, don’t need to go anywhere, do you?

Gordon Freeman can try crawling around to evade the murderous tentacle beasts in Half-Life or lob grenades to distract it. Now that I think of it, Half-Life also has those trees which stab you if you bump into them. And then Half-Life: Alyx had Jeff, an invincible giant lad drawn to sound, which produced a whole deadly stealth section of lobbing bottles and holding your cybergloves to your meatface to stifle coughing. Very good. These enemies can even be frenetic combat puzzles, like Resident Evil 4’s fights with the giant Wolverine boys, where you keep switching through sneaking, shooting bells to distract them, and unloading your shotgun into their spine. And Minecraft’s Warden can not only feel your vibrations, it’ll sniff around to find you too. Rude. I’m sure you can tell me about many more su hmonsters.

The most important thing is: forget all the instincts you had developed playing the rest of the game. Do not shoot on sight. Do not sprint about. Do not jump everywhere because you like the noise. And oh mercy, please resist the urge to destroy every destructible object.

I also like how this often encourages me to doubt my understanding of a game. We’re always playing our own internal model of a game as much as we’re playing the game, testing boundaries and feeling out possibilities until we think we think we know how it works, and we play within those confines. But when an enemy who supposedly can’t see you wanders right past, maybe even turns their head in your direction, how confident are you that they truly can’t see how? Do you truly trust that the developers wouldn’t try to trick you?

I think I most enjoy when these enemies are mild puzzles, not just tests of patience. There are many reasons why Aliens: Colonial Marines isn’t as good as Half-Life: Alyx, but that certainly is one.

Enemy which only moves when you’re not looking

It’s a horror classic: a doll, mannequin, statue, or other unmoving thing which does, in fact, move—but only when you’re not looking. Turn your back and oh, was it always in this pose? Turn again and hang on, is it closer? Yes, it is. It’s coming for you. How well can you watch it while managing everything else you need to do?

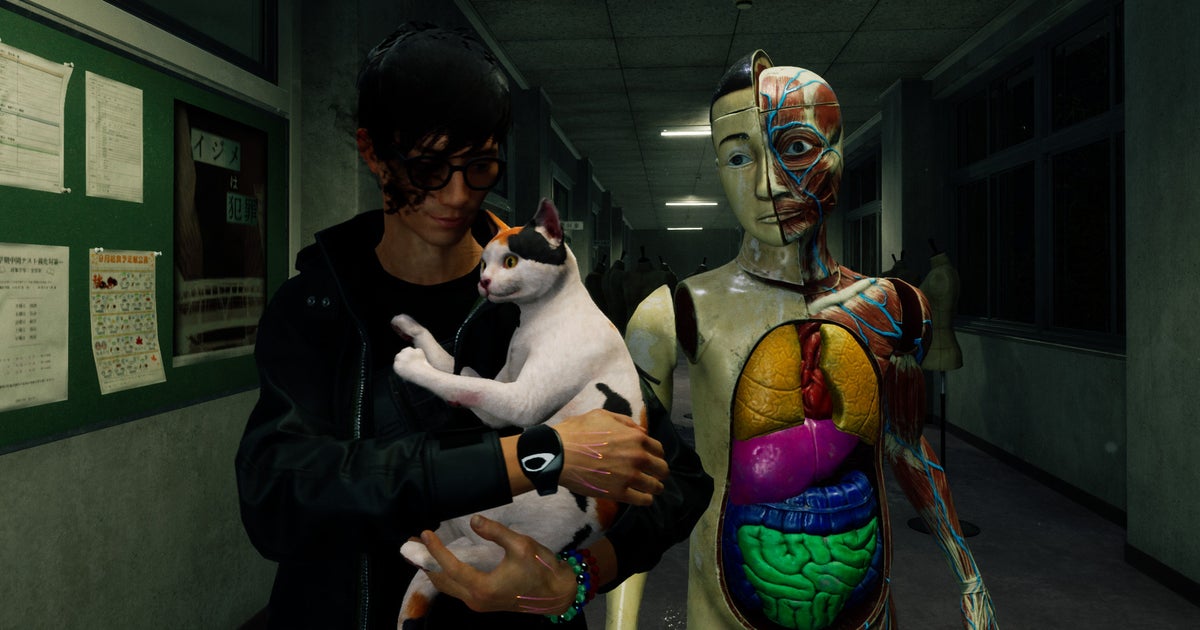

Doctor Who’s Weeping Angels, which look like statues from a goth’s garden, are maybe the most famous modern example of this. You’ll find them in Doctor Who games, obvs. Ghostwire: Tokyo added a horrible life-size anatomical model for a quest in a recent update, who’ll follow you around, bang furiously on doors, and pretend he was just hanging out when you open them. Resident Evil Village’s Shadow Of Rose expansion had not just one horrible giant doll but several, all at once. That horrible giant bowling pin baby made famous by SCP is in so many SCP fan games (though officially SCP-173 no longer looks like it). The Forgotten City does it a little, though harmlessly (well…). And just yesterday, I was playing a fun short horrible mannequin game.

It’s a good wrinkle to throw into a game. You’re comfortable moving and looking, ready to shoot or solve puzzles or find stuff or whatever it is you do, and now you have this whole new terrible thing to factor in. Two of the most unconscious actions in games are now pieces of an ever-changing puzzle you must continuously solve to stay alive. I like when games make the unconscious very conscious.

This type of enemy is also the foundation of Five Nights At Freddy’s. I can’t say I’m a fan of the jumpscare ’em up series but I am delighted by its fan scene. It inspired many, many players to try their hand at making games inspired by it. For a while, I kept count with a list, stopping in 2015 at 1139 Five Nights At Freddy’s fan games hosted on one site alone. I couldn’t even tell you how many thousands more than are now, because Game Jolt search stops counting results when it hits 10,000. More than 10,000. I wouldn’t be surprised if you could add another digit or two to that.

In some games, these vision-locked enemies might continue moving for a little bit after you spot them, a spurt of movement as they round a corner, the end of an animation before they lock into place. I’m often not sure how to take this. Sometimes this feels like a bug to me, and it detracts from the experience. But sometimes it does feel intentional, inspiring that same sinking feeling I get with unseeing enemies, “Maybe… maybe they don’t quite work the way I think they do.” That could flip my understanding of these dolls and statues from being bound by supernatural logic to merely pretending to be so they can toy with me, which is far worse. I hate it, and it’s great.

But which is better?

I like these moments when looking becomes my most powerful weapon and my greatest weakness. Yeah I’ve got guns and knives and magic spells, but a good hard stare, that’ll sort them out. If only I remember to keep looking. But which do you think is better, reader dear?

Pick your winner, vote in the poll below, and make your case in the comments to convince others. We’ll reconvene next week to see which thing stands triumphant—and continue the great contest.

Credit : Source Post